Trigger warning: this issue focuses on a news article/ study about intimate partner violence.

Welcome to the 18th edition of Developmental Insights! In this edition, we will delve into visas in the UK, gender crimes in Afghanistan, rights for children in Kenya, IPV in Australia before finally landing in Honduras to explore elections.

For this edition’s ‘In Discussion’, I thought that I would try something new. Rather than doing a deep dive into an article that I had found in the two week period between posting the newsletter, I thought that I would write and share something that I had been researching. I hope everyone else finds my deep dive into slum tourism interesting and if there’s any topics/ subjects you feel I should focus on, please let me know in the comments or email developmentalinsights@gmail.com.

In this edition:

Changes to family reunion visas will leave women and children in war zones

The Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has temporarily suspended the UK’s family reunion visas for refugees while it undergoes review. This policy move could leave women and children stranded in conflict zones. 92% of family reunion visas were granted to women and children, with over half going to children in the year to 2025, predominantly from Syria, Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iran, and Sudan.

Refugee policy experts have warned that this route has not been one of the safest ways for vulnerable families to reach the UK and suspending it could lead to further problems, such as forcing families into dangerous migration paths. Under the current system, refugees awaiting a family reunion are restricted from working and are dependent on minimal daily support, something which leaves them financially constrained.

Gender Apartheid as an International Crime

Since the Taliban’s takeover in August 2021, Afghan women and girls have faced systematic repression including bans on education, prohibitions on paid work, travel restrictions and bans on singing and simply speaking in public. These women have also become isolated from the outside world, with the Taliban forcing donor support to dwindle. These measures have been described by many as a ‘gender apartheid’, reflecting a structural regime characterised by oppression and segregation.

In response to this, Afghan’s women’s rights defenders are urging the United Nations to recognise gender apartheid as a distinct international crime in the upcoming crimes-against-humanity treaty that is currently being negotiated at the UN General Assembly. Advocates have argued that this treaty is a critical legal gap and that it needs to be passed so that the Taliban can be held accountable.

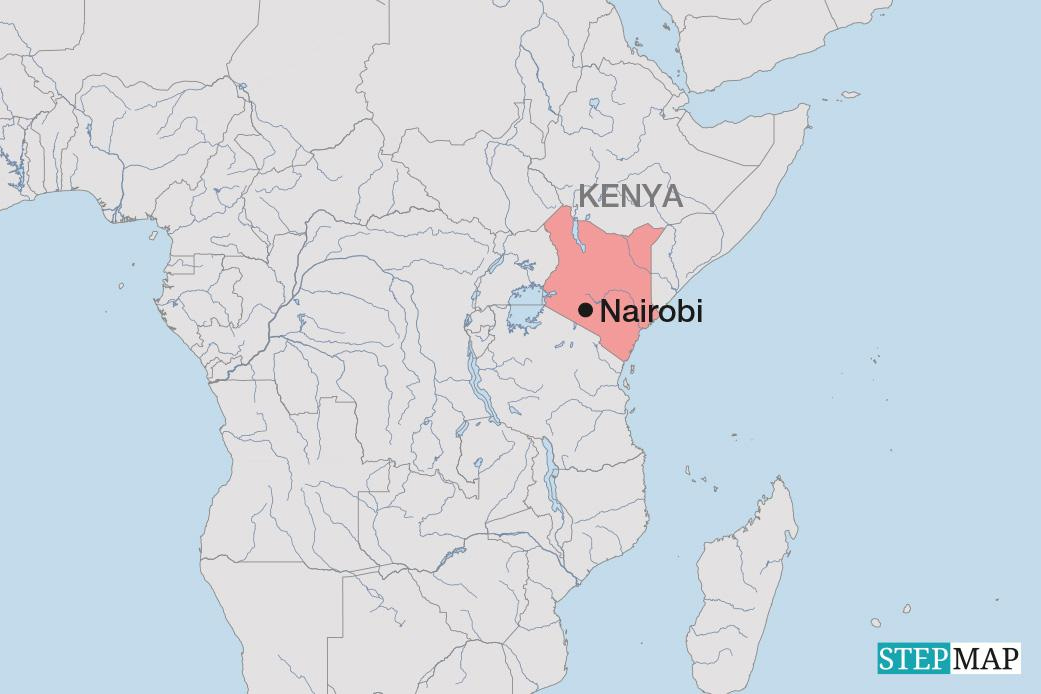

Kenya upholds inheritance rights for all children

This year, Kenya’s Supreme Court delivered a landmark ruling affirming that children born outside of marriage would have access to equal inheritance rights. By a majority of five out of seven judges, the Court prioritised constitutional protections over religious or personal laws. This emphasises that the marital status of the parents should not dictate a child’s right to inherit, declaring it as ‘unreasonable and unjustifiable’.

The decision rests on the supremacy of Articles 27 and 53 of the country’s Constitution, which guarantees equality before the law and prioritises best interests for children. Religious customs must also conform to constitutional norms when fundamental rights are at stake.

Trigger warning: the following story focuses on intimate partner violence.

1 in 3 Australian men admit to intimate partner abuse

A study by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) has found how 35% of Australian men aged 18-65 reported using intimate partner violence (IPV) at least once in their lifetime. This figure is up from 24% in 2013/14. The survey, which included around 26,000 men, categorised IPV to include emotional abuse (admitted by 32% of respondents) and physical abuse (admitted by 9% of respondents). Nevertheless, this figure only represents those that participated so it could be much higher.

The research also highlighted key protective and risk factors. Men that had affectionate childhood relationships with the fathers/ father figures were 48% less likely to perpetuate IPV, while high levels of social support were associated with a 26% lower likelihood of IPV usage. Furthermore, those with moderate to severe depressive symptoms or histories of suicidal ideation/ attempts were significantly more likely to engage in IPV. These findings make a strong case for early mental health intervention, strengthening social connections and encouraging positive father- son relationships as significant pathways to prevent IPV.

Hondurans right to free and fair elections

In November of this year, Hondurans will be taking to the polls to vote for their president, members of the National Congress and representatives to the Central American Parliament. Despite this being a huge event, the integrity of the election is in jeopardy. The primary held in March 2025 was spoiled by significant logistical failures with ballot boxes being delivered hours late in key cities like Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, forcing delayed or repeated voting. Such disruptions delayed the implementation of the preliminary results transmission system (TREP), and the Attorney General has launched investigations into council members for alleged crimes, increasing fears of excessive judicial interference in the electoral process.

The Human Rights Watch has urged urgent attention internationally to safeguard Hondurans’ electoral rights. The current political dynamic of the country puts fairness and transparency at risk, threatening democracy. External observers and support mechanisms are essential to help ensure that the elections can proceed without intimidation, manipulation or systemic failure.

In Discussion:

For this edition’s ‘In Discussion’, I thought that I would share something that I have been reading up and researching on. Slum tourism is a fascinating practice and focuses on the concept of tourists - generally from the Global North - travelling to the South and intentionally visiting and ‘touring’ impoverished areas.

My article ‘The Paradox of Slum Tourism’ introduces the practice before exploring both sides of the debate and using Soweto township in South Africa as a case study.

The full article is also linked on my personal website.

The Paradox of Slum Tourism

Companies like Get Your Guide and TripAdvisor boast a variety of slum tours, enabling enthusiastic and excited travellers to experience what it is like to live in these places. Given titles like ‘Nairobi: Explore Kibera Slum with Local Guides’ or ‘Mumbai: Dharavi Slum Walking Tour with Local Slum Dweller’, individuals are promised opportunities to ‘live and work’ like a local, discover ‘innovative items made in tiny spaces’ and ‘marvel at the residents’ genius’ for as little as £6.

Slum tourism involves tourists - usually from the Global North - intentionally going into impoverished neighbourhoods or slums - usually in the Global South. Driven by pure curiosity, and the desire to be self- reflective, these opportunities enable them to contrast their lives with those that live in economically impoverished areas. Over the decades, this practice has been viewed as a paradox. On one hand, it has attracted much scrutiny for being neo-colonial and romanticising negative stereotypes of poverty, while on the other, recent debates have found that it is a positive way to generate local business. This article will delve into the phenomenon before using Soweto township in South Africa as a case study.

The United Nations has defined ‘a slum’ or an ‘informal settlement’ as a group of individuals that ‘live in the same roof in an urban area which lacks one or more of the following:

Durable housing of a permanent nature that protects against extreme climate conditions.

Sufficient living space which means not more than three people sharing the same room.

Easy access to safe water in sufficient amounts at an affordable price.

Access to adequate sanitation in the form of a private or public toilet shared by a reasonable number of people.

Security of tenure that prevents forced evictions.’

The practice which involves visiting slums as a recreational activity began in Victorian London. Upper classes, politicians, academics, social reformers and journalists amongst others ran these tours, which, over the next 100 years began formalizing to what we know of it today. Today, they are run by private tour companies, charities and non-governmental organisations and are understood to be an activity where tourists from the Global North visit impoverished urban centres in the Global South.

The Controversy

Viewed as neo-colonial, slum tourism has been criticised for perpetuating ideas of despair and misery, along with romanticising poverty. In this, they feed into stereotypes that conceal many of the daily problems which the people living in these areas face. A study by the University of Bath which analysed TripAdvisor reviews of slum tours in South Africa found how only four of 452 reviews commented on water, sanitation and sewage within townships. As a result, reviews present residents as satisfied living situations, something which renders it as acceptable. These opinions also ‘mask’ systemic issues such as social, economic and political challenges, portraying them as the norm in the Global South.

A Positive Way to Engage with Cultural Experiences

On the other hand, slum tourism has also been presented as a contribution to the local economies of Global South countries. Eager eyed tourists are attracted to cultural experiences which differ to their everyday lives and their spending enables employment and growth to be created in marginalised areas. Not only can they contribute to tours themselves, but they can also purchase local goods such as food and souvenirs. Those that live in such areas are also able to gain the support they need in building their own businesses, fostering self-empowerment and mobility. The practice can also help debunk some of the negative perceptions that these areas have, enabling knowledge to be gained and then spread back to where tourists have come from.

Case Study on Soweto Township, South Africa

Advertised in Getaway Magazine, slum tourism has described the activity in South Africa as a ‘significant sector within the South African tourism industry’. This is because it provides visitors with the opportunities to engage with local communities and experience cultural practices along with understanding the historical context behind such areas. Slum tours in their current embodiment began in South Africa in 1991 when apartheid was at full force. Visitors to the country were directed to townships and non-white areas in major cities such as Cape Town and Johannesburg.

One such township is Soweto, located in Gauteng Province and is the country’s largest Black urban complex. Created during apartheid by the white government in the 1930s to keep blacks away from white suburbs, the township represents the ‘politics of poverty and segregation, the struggle for democracy and the spiritual emptiness of [the country]’. Soweto developed from the shantytowns and slums which were made when Black labourers from rural areas went there in the period between World Wars I and II. It has since been the spearhead for the demands towards Black equality during apartheid, been the site of the Soweto rebellion and has the only street in the world where two Nobel Prize winners once lived (Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu).

In 2002, Soweto was incorporated into Johannesburg, and today, it is a vast neighbourhood, home to around 2 million people. A township of contrasts, some communities face social and economic problems with poverty being the most prevalent. Parts of Soweto lack access to electricity, clean water, infrastructure and sanitation, all of which negatively impact the quality of life of those that live there. Schools also suffer from a lack of infrastructure and tend to be overcrowded, with drop out rates high.

Despite this, slum tours in Soweto are rampant. Between 200,000 and 300,000 tourists visit the township annually, coming mostly from the United States, the Netherlands, Germany and South America leading this. Although this does have many economic benefits such as job creation (through tours as seen on sites like Get Your Guide and Trip Advisor) and support for local business, largely there was a disruption of family or community life and an overcrowding of amenities.

The practice of slum tourism is a paradox within itself. While it can generate income and support local business, it risks turning poverty into a commodity, reinforcing stereotypes and obscuring the systemic inequalities that residents face. Soweto’s example shows how tours can both empower communities and disrupt daily life, highlighting the practice’s dual nature.

As always, thanks for reading edition 18 of Developmental Insights - I hope you enjoyed it and found it informative! Please subscribe to the newsletter if you would like to continue receiving it straight to your inbox every other Friday!

I am always open to suggestions or feedback so please send anything to developmentalinsights@gmail.com or, simply add a comment below!

I look forward to connecting with you further in future editions!

Best,

Harkiran

Really interesting read Harkiran! The slums tourism was quite interesting never even knew that was a thing !